Russian Dress

in IX-XVII Centuries

(with Focus on Women’s Dress)

Collegium Caidis Notes by Liudmila Vladimirova doch’

with the editorial assistance of Mistress Soraya Evodia, O. L.

Part One

Early, or Kievan, Period: IXth through XIIIth Centuries

Sources

So far,

archeologists have not found complete pieces of ancient Russian clothing from

the IX-XIIIth centuries, only parts and decorations. These serve as primary

sources for the study of Rus' costume, along with the pictorial material of

frescos, illuminations, icons, and decorated objects. These materials can be

compared to the written sources (chronicles, lives of saints, various deeds and

wills) and to the later period clothing to establish the terminology and learn

about construction. (Rabinovich, p. 40.)

Application

of modern research techniques to the ever-growing fund of archeological

evidence allows for better understanding of materials and techniques used in

making ancient clothing, according to Rabinovich. Newfound evidence, such as a

group of ritual metal bracelets with various male and female figures on them,

provides valuable clues as well.

Fabric and other materials

The

majority of the population wore shoes and clothing created of homemade

materials. In most families, women spun and wove flax, hemp, and wool at home,

as evidenced by numerous archeological finds of implements for these crafts.

(Rabinovich, p. 41.) Linen was woven on a horizontal loom, in simple weave or

in complex patterns, ("bran,"

damask). The thickest linen (or hemp) fabric was known as "votola" and used for outer wear,

the thinner though still coarse fabric as "tolstina" (for thickness) or "uzchina" (for narrow width), while the finest bleached linen

was called "poniava" or

"bel'." Coarse woolen

fabric destined for plain coats was "sermiaga,"

while finer wool was called "volosen."

Like linen, wool was woven either plain or in patterns. By the XIIth century,

woolen checkered fabric, later known as "ponieva," became widely used. (Rabinovich, p. 42.)

According

to the frescos, noblewomen's clothes in that period were brightly colored, with

red favored above other dyes. More than half of all fabrics found in

archeological digs is some shade of red. (Pushkareva, p. 161.) However, green,

blue, and yellow were also frequent. Dark, somber colors, especially black,

were reserved for mourning and for widows. Rabinovich (p. 42) maintains that

linen fabrics were mostly white, while wools were either natural or brightly

dyed in the colors mentioned by Pushkareva.

Very

expensive fabrics such as silks and gold brocades were imported from the East

or from Byzantium.

All such fabrics were known as "pavoloki,”

(Giliarovskaia, p. 123), though they also had separate names. While the upper

classes could have a whole garment made of those fabrics, the commoners could only

afford to use small pieces for decoration. (Rabinovich, p. 42.) To compensate

for the lack of rich adornments, homemade fabrics were often block-printed

("naboyka") in repetitive

geometric or simple floral patterns, using blue or black paints. (Giliarovskaia,

p. 122.) Naboyka was not excluded

from the rich homes either, though its most common use there was as lining.

Furs and

animal skins were widely used to make outer clothing, and as linings and trim.

Leather footwear (tanned or not) replaced bark and bast, ancient materials for

Slavic footwear, for all but the poorest in the Xth century. While the

production of leather remained a household chore in the countryside, in the

cities it was developing as a separate craft. (Rabinovich, p. 42.)

Women's clothing

Dress was

subdivided into undergarments and overgarments, which were often similar to

each other in cut, but not in decoration. The undershirt, or "srachitsa,” is mentioned in many primary

sources of the X-XII centuries. Srachitsy were made out of bleached linen, thin

wool, or even silk, and cut long and straight with triangular gores widening

the hem and diamond-shaped gussets inserted under the arms. The sleeves were

usually narrow and longer than arm length. They were pushed up on the forearm, held

at the wrist by hoop bracelets ("naruchi")

during everyday activities, and let out for holiday occasions/dancing. Women

dancing with their sleeves dangling can be seen on bracelets from the XII

century, and the Russian fairytale of the frog tsarevna (princess) has an episode that takes advantage of

extra-long sleeves. The neck opening was small and round or, rarely, square,

with a straight short slit in the center or offset to either side, buttoned or

tied at the top (Rabinovich, p. 43; History

of Ukrainian Costume, p. 25). The question of whether the undershirt was

belted is still debated, though prevalent opinion is that it was. If there were

belts, they were decorative lengths of trim or twisted cord, not leather.

(Rabinovich, p. 44.) The hem of the undershirt was often embroidered in red,

though the designs and technique of this embroidery appear to be lost now.

(Pushkareva, p. 156.) Rabinovich also suggests decorative appliques of

different colored fabrics along the hem, at the neck, and on the sleeves of

women's shirts.

The

undershirt was most often topped with "ponieva"

- a garment most likely worn around the waist like a wrap skirt. Again, there

are no actual surviving examples of complete ponievas in early period. Later ponievas

were made of plaid woolens and consisted of three panels gathered at the waist

without side seams, or sewn only a short way down. However, many authors

believe that the early ponieva was of

one-piece linen fabric, possibly even the same color as the undershirt, held at

the waist by a knitted woolen belt. (Pushkareva, p. 157.) Rabinovich (p. 44)

supports the notion that the name "ponieva"

for a checkered wrap skirt appeared no earlier than the XVIth century.

The History of Ukrainian Costume (p. 25)

discusses a maiden's garment, "zanaviska,"

while proposing that only married women could wear a ponieva (which was certainly true in later times). The same garment

is described by Kireyeva (p. 8) as "zapona."

Zanaviska or zapona was a tabard-like garment, made simply of a folded length of

linen with a round opening for the head. The sides were left unsewn, and either

pinned together at the waist, or tied up with a belt. Note that neither ponieva nor zapona were, at this time, required elements of clothing - a shirt

alone, or with another, fancier overshirt ("navershnik") was sufficient for the lower classes anywhere and

for nobility at home.

Surviving

frescos and chronicles indicate that noblewomen of that time wore loose,

straight dresses with wide sleeves, made of imported silk and brocade, richly

adorned along the hem and round collar with gold trim. These dresses were worn

belted with fabric belts, (not leather), embroidered in gold or made of gold

cloth or trim, and were usually shorter than the undershirts. Over the dresses they

draped rectangular capes, similar to men's, also richly adorned and lined.

It should

be noted that these dresses are often referred to as "dalmatics,"

alluding to Byzantine influences. While there were, of course, such influences,

Pushkareva insists that Russian clothes of that period were closely related to

that of earlier Slavs in style and still had three distinctive types. These

types were "nakladnyie" -

put on over the head (rubakhas, dresses), "raspashnyie" - buttoned up the front (coats), and draping

(capes). The known examples of ornamentation designs are also distinct from the

Byzantine and persistent through the centuries. The same patterns are found in

early frescos and ornaments, later illuminations and embroideries, and

post-period embroideries.

Embroidery

was used both as decoration and as protection from evil, guarding all openings

of the garb. (Rabinovich, p. 61.) Clothing was often embroidered with gold

thread in stylized flowers and grasses, circles, and geometric patterns. Early

embroidery (up to the XII century) brought the gold thread through the fabric,

with short stitches on the inside and long on the outside. (Pushkareva, p.

161.) Later, gold thread was couched down with silks. During this period,

pearls were not used as freely as in later times, but applied sparingly, in

single grains or as outlines of silk-embroidered ornaments or metal plaques. (History of Ukrainian Costume, p. 17;

icons from Giliarovskaia.). Furs were often used for decoration as well, with

stripes of fur along the hem often wide enough to reach the knees. (Pushkareva,

p. 160.)

Women's Headwear

Rabinovich

(p. 47) suggests that the custom of married women covering their hair, and the

underlying superstition that seeing their uncovered hair can lead to harm, have

roots in pre-Christian Slavic beliefs. In XIIth century Novgorod, anyone who pulled off a woman's

head covering so that she became "prostovolosaya"

(plain-haired) was punished with a very high fine for shaming the woman.

(Rabinovich, p. 47.) This head covering was usually a "povoy," later known as "ubrus," - a towel-like veil closely

wrapped around a woman's head and secured with special pins. Some archeological

finds suggest that povoi could have

special weights sewn to their edges to make them hang better. (Rabinovich, p.

47.)

The

evidence in support of more complex headdresses in that period is fragmentary,

though there are numerous reconstructions based on the available parts.

(Rabinovich, p. 47-48.) It appears, however, that headdresses similar to later kokoshniki on stiff foundations and

softer kiki with stiffened decorative

front parts existed before the XIIIth century, and certainly before names such

as "kokoshnik" and "kika" appear in written documents.

While povoy were spread all over the Russian lands, kokoshnik was found mostly

in the North, and kika - mostly in the South.

Maidens had

no head covering restrictions, and usually wore their hair loose or braided in

one or two braids. The hair was held in place with a "venchik" (later - "venets"),

a narrow metal diadem or a narrow strip of bright, decorative fabric tied at

the back. Rabinovich (p. 47) refers to more complicated, highly ornamental venchiki as "koruny," and mentions remnants of such koruny found in treasures buried before the Mongol invasion.

Neither venchik nor koruna covered the top of the girl's

head or her long hair.

Jewelry

Women's and

girls' heads were probably the most ornamented parts of their figures. Various

metal decorations were attached to their headdresses, braided in their hair, or

used as earrings. Most such flat decorations are known to archeologists as

temple rings. (Rabinovich, p. 52.) The design of the temple rings varied by

region. For example, for Slovenie in Novgorod

they were made as large rings with diamond-shaped decorations. Viatichi,

residents of the Oka valley, wore seven (3 on

one side of the face and 4 on the other) seven-bladed rings. West of them,

Radimichi wore similar temple rings with seven beams on each. Still farther

west, Severyanie wore temple rings made of wire spirals. In many tribes, women

wore one or two small wire rings, while Drevlyanie, who lived in the Volyn

region, wore multiples of such rings. In Polesie, Dregovichi wore temple rings

with added granulated copper beads. However, beginning in the XIIth century,

the temple rings begin to lose their regional specificity. For example, temple

rings with three smooth or lacy beads, produced in Kiev, were known all over the Ancient Rus'

territory. Rabinovich (p. 55) suggests that this was a result of the city

fashion's influence over the tribal customs.

Strings of

beads were another decorative element of women's costume that used to be

tribe-specific and then became common due to the development of city

craftsmanship. Early on, most beads were imported, but while some were popular

across all Eastern Slavic lands (such as the Middle Asian blue glass beads

known as "fish-like beads"), many became particular favorites of one

tribe or the other. Thus, Novgorod Slovenie preferred multi-faceted crystal and

silver beads, while Viatichi wore pink double pyramids of "serdolik" and white balls of

crystal or glass. The styles became more uniform as bead making developed in

Russian cities. (Rabinovich, p. 55)

"Kolty" also developed in the

cities. Kolty were hollow metal

ornaments (shaped something like closed clamshells or flat balls) decorated

with enamel, granulation, or blackening, and secured to the headdress at the

temples. Sometimes larger kolty had

chains of smaller medallions dangling from them at the sides of a woman's

headdress.

Women also

wore "grivny" - torques,

various bracelets, and rings. Unlike the Western torques, grivny were at least sometimes worn with the opening at the back,

since the front parts of them were most ornamental. (See Rabinovich, ill. 13,

p. 54, for a grivna with a twisted

front and plain back). Pushkareva (p. 167) mentions round wire, scaly, and

twisted grivny, with regional

preferences for some of the types. Most commonly, grivny were made of copper or bronze, with the most expensive ones

fashioned from a silver and copper alloy. The bracelets were most popular in

the cities, with metal hoop bracelets used in ancient times supplemented in the

XIIth century by wide hinged silver bracelets that depicted ritual dances and

fantastic animals. (Rabinovich, p. 57.) Hoop bracelets of colored glass were

worn by rich or poor city women, sometimes with several of them on each arm.

Rings were popular with either city or country women, and could be decorated

with enameling or filigree.

Footwear

Rabinovich

(p. 48) refers to the footwear during the IXth through XIIIth centuries as

being made of bark, leather, and perhaps even fur, never cut from wood as known

in the West. The most common form of men's and women's footwear was woven from bark

or bast. Such shoes were known as "lapti"

or "lychaki" ("lyko" is "bast" in Russian), and

were made by Eastern Slavs long before the

IXth century. Lapti were worn

predominantly by the peasants, and a chronicle of 985 (as cited by Rabinovich,

p. 49) contrasts lapti-wearing

peasants to the city dwellers who wore "sapogi" - leather boots. Still, lapti-type footwear was worn in the cities as well, but there it

incorporated leather strips, woven either together with bast or on their own.

This modification was most likely due to the brief useful life of bast lapti - 10 days in winter, up to 4 days

in the summer, and probably even shorter on the paved streets. Despite this,

there probably existed lapti for the

rich made of silk ribbons, for special wear.

Like many

other elements of clothing, lapti

differed by region. In Western Rus' (later Ukraine

and Belorussia), lapti were of straight weave, while in

the Eastern Rus' they were of diagonal weave.

Thus, Radimichi, Dregovichi, Drevliania, and Ploianie had straight-woven lapti, while Slovienie (Novgorodians)

had diagonal-woven birch bark lapti,

and Vyatichi (Vladimir, later Moscow region) had diagonal-woven bast lapti.

"Porshni" were the simplest kind of

leather shoes. According to Rabinovich (p. 50), porshni were commonly made from a single rectangular piece of

leather (not tanned, just kneaded and oiled). The corners of a rectangle were

connected in pairs, and a leather thong was then threaded around the top edge. Porshni made from two pieces of leather

are found by archeologists more rarely than those made from single pieces.

Rabinovich also speculates that early porshni

were made not of leather but of untreated animal skins. Sometimes porshni were decorated with cutouts or

embroidery, in which case they could be lined (Pushkareva, p. 173). Even

decorated, porshni were shoes for the

peasants or the poor.

Both lapti and porshni were worn over "onuchi,"

the leg wraps. They were secured on the lower leg by long leather strips or

hemp cords crossed several times along the leg. On many pictorial documents of

the time, diamond patterns resulting from this can be seen on the legs of

people wearing lapti or porshni. (Rabinovich, p. 50.)

Richer

peasants and many city residents wore "chereviki"

- leather shoes made from several pieces of leather, with sewn-on soft soles

and the edges covering the foot to above the ankle. In the front, the edges at

the top were separated to allow for freedom of movement (see pictures). Unlike lapti or porshni, chereviki were

most likely made by professional shoemakers due to their complexity.

The

remnants of sapogi are found in the

archeological digs of the cities much more often than any other footwear. Sapogi of this period had soft

multi-layered leather soles, slightly pointed or round toes, and ended below

the knee. The top edges were cut on a diagonal, so that a sapog was higher in

the front than in the back. Sapogi

were made on a wooden form without side differentiation, with seams on both

sides of the leg. Dressy sapogi were

adorned with fabric cuffs and embroidery in silks or even pearls, and for the

rich came in better kinds of leather and in a variety of bright colors - red,

yellow, green, etc. (Rabinovich, p. 51.)

Brief notes on men's clothing

|

Men wore

the same kind of a shirt, "srachitsa,"

as the women. A man's srachitsa was knee-length or longer, worn over his pants

with a narrow leather belt (with a metal buckle and metal plaques for

decoration) or a tasseled cord. Like women's, men's shirts were commonly

decorated with embroidery at all openings. The pants, "porty," were narrow around the legs

and wide at the waist, with a gore inserted at the crotch. The top of the porty

had no slit, and was secured around the waist with a drawstring ("gashnik"). Porty reached below the

knees but above the ankles, and were always worn inserted in sapogi or onuchi. For the poorest,

srachitsa, porty, and onuchi (or woolen socks, "kopytsa") were all the clothes they wore at home or at work in

the summer.

Very little

is known about the outerwear of Ancient Rus'. Written sources of the period

mention "svita" as men's

clothing worn over the srachitsa. Rabinovich (p. 45) speculates, based on

period pictures, that svita at this

time was long, form-fitting, and could have a decorative fold-down collar and

cuffs. It had a slit at the top, opening to about the waist level.

Giliarovskaia (p. 65), referring to a similar garment as a "Kievan

kaftan," suggests that this could be women's clothing as well, in which

case it was longer and with wider sleeves (to show off the undershirt). |

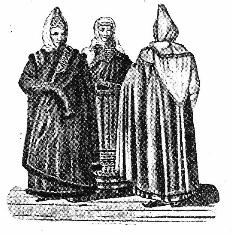

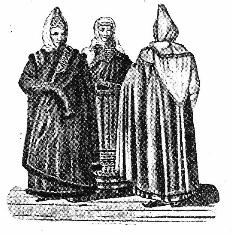

The most

common cape-style clothing, "votola,"

was made of the coarse linen or hemp cloth of the same name. It was a

knee-length or ankle-length cloak (possibly hooded) worn over a svita and fastened at the neck with

cords (for the poor) or special fastenings like fancy safety pins

("fibuly"). Period documents mention several other kinds of cloaks,

such as "myatl'," "kisa," or "kots', " but their cut and design

are unknown (Rabinovich, p. 45). There was also a special cloak worn only by

the Dukes, "korzno." The korzno was very long, to the heels, and

fastened at the right shoulder so that the left arm was hidden, and the right

arm was free. Giliarovskaia (p. 66) suggests that the korzno made of especially heavy brocade had a cutout for the left

arm (see picture). Korzna were made

of rich Byzantine fabrics, often with some fur trim.

In the

winter, men and women both wore "kozhuhi,"

forerunners of later "shuby."

Kozhuhi were made of animal skins,

with the fur on the inside. For the poor, they were sewn from sheepskins and

left unadorned. For the rich, they could be covered in imported fabrics, and/or

decorated with gold metal lace and stones. It is likely that the nobles wore

their kozhuhi when it wasn't cold as

well, to show off the fancy furs and the rich decorations. (Rabinovich, p. 46.)

Men's pre-XIVth century headwear is

not well known, since most pictures show the men bareheaded, especially if a

Duke is in the picture. Rabinovich (p. 46) and Giliarovskaia (p. 82), based on

limited evidence, speculate that men wore round or pointed hats made of fur or

felt, or woven of roots or straw. The ducal hats are studied better. Their

traditional and persistent shape through the ages was a hemisphere made from

bright fabric, with a fur border. This design is reflected in the famous

"Monomakh Cap".

Part Two

Late, or Muscovite, Period: XIIIth through XVIIth Centuries

Sources

There are few surviving examples of

clothing from that time period. Mostly church vestments survived from before XVIIth

century, though the researchers suspects that some items in XVIIth

century collections were made in XVIth century. There are several

shirts, found in burials, that are dated precisely to the XVIIth

century. Thus, archeological material is not as substantial for this period as

for earlier ones.

Though Russia, unlike

Western European countries did not have portrait painting developed until the

late 1600s, there is substantial pictorial evidence for clothing of that time.

It is mostly found in miniatures from manuscripts, icons, and drawings in

journals of foreign visitors. The later, however, are often suspect, because

pictures in them are often incorrect.

Most

numerous are the written sources, such as various wills, dowry inventories,

pleas, merchants’ ledgers, and, again, foreign travelers’ journals. The

surviving illustrated ABC books provide invaluable clues for matching terms

found in written sources to pictures and objects.

Fabric and other materials

The dress

of peasants and commoners was, as earlier, most often produced of homemade

linen and wool. Later in period homemade cotton fabrics appear as well. Linen

or cotton basket-weave fabrics were known as “holst,” and could be bleached or

dyed in various colors, or even block-printed. There was also fabric of a more

complicated, ornamental weave, known as “bran’,“ and apparently similar to a

two-color damask. Homemade woolen fabric, as well as clothing made out of it,

was known as “sermiaga.” Until the XVI century woven plaid

fabric, “ponieva,” remained in

widespread use, which was probably diminished when a “ponieva” skirt made of it was displaced by other garments.

The

assortment of imported fabrics for the rich was very broad, with more than 20

kinds of silk and cotton fabrics imported from the East listed in various

period sources. Wool was imported mostly from Western

Europe, with over 30 varieties of it known in period. However, in

XVIth century cotton, wool, and silk fabrics of quality were produced and dyed

by Russian artisans as well.

Red

remained the favorite among clothing colors, with black gaining use, followed

by yellow, green, and dominating white of shirts and other underwear. Black,

however, appears to be used mostly by older people, widows, and those in

mourning, unless it was richly decorated with embroidery and trim.

Furs, of

course, were widely used throughout Russia, as well as exported.

Commoners used sheep, while the upper classes could afford fancy furs. Leather

of various origins (goat, sheep, cattle, and horse) was used for shoes, belts,

sheaths, and purses.

Undergarments

Both man

and women, as before, wore tunic-like shirts (“srachitsa,” “sorochka,”

or “rubakha”). Women’s shirt was

always long, to the feet, and so were the shirts of children of both sexes.

However, adult peasants wore their shirts to the knees, and city dwellers even

shorter. Men commonly wore “porty,”

narrow simple pants, as well. This period saw the shirt actually turn into

undergarment, because it became improper to wear it alone. Thus, two shirts were

worn at a time, with a fancier one covering the plain undergarment. The outer

shirt was known as “koshulia,” “verhnitsa,” or “navershnik.” Navershnik

is a better known type, described as a tunic-like feminine garment with wide

sleeves, shorter than the undershirt.

The shirts

were very simply cut from a whole length of fabric, without waste. The body was

built of folded length of fabric, without shoulder seams. The neck opening was

cut around at the fold. Since the fabric was not broad enough, rectangles half

as wide as the fabric were inserted in the side seams, often with additional

gores at the bottom of all four resulting seams. The sleeves were narrowing to

the wrist, with triangular gores widening them along the upper arm.

Diamond-shaped gussets, often red, were inserted under the sleeves. Oftentimes

a triangular “podoplieka” was sewn

from the inside to the shoulder portion of the shirt, to make it sturdier. In

male shirts, there was a slit at the bottom of the shirt’s front.

At least on

the noblemen’s shirts, all seams were adorned with red and gold trim, red

ribbon, or embroidery. The seams themselves were done in double lines of red

silk on top of the two folded edges placed one over another. Sleeves were

adorned with “voshvy” – applied

rectangles of fabric with vertical slits, with slits sometimes made in the

garment itself as well. Voshvy, neck

slits, and bottom front slits were decorated with embroidery and/or applied

trim in horizontal rows. Rows of trim formed loops and knots at the openings, which

allowed to button up the slits. The neck openings were held together with

decorative cord ties. (T. N. Koshliakova)

Women’s clothing

Women wore

a shirt with some type of an overgarment. Earlier in period, it was (at least

for lower classes) described earlier ponieva.

By late XIVth century, it was replaced in the cities by sarafan-like garments. Sarafan

is probably the most debated garment in this area of research, since there is

no clear connection between the dress itself and the name “sarafan.” Until the XVIIth century, “sarafan” or “sarafanets”

is found in sources as a name for men’s long garment that buttoned up the

front. However, there are period names (“shushun,” “shubka,” “sayan,” “feriazi,” etc.) for a women’s dress put

on over the head that later co-existed with “sarafan” as terms for women’s light clothing worn over a shirt.

Thus, what later became known as “sarafan”

probably existed in period in some form, but by other names. The researchers

suggest that it evolved either out of a lengthened ponieva that acquired straps, or out of a dress that lost its

original long sleeves, with later view more prevalent. Still, there are no

surviving items or verified pictures that could document the cut of this

garment clearly. Note that any future use of the word “sarafan” in this paper will refer to the variety of garments with

the names given above.

“Shubka” (not to be confused with “shuba,” a winter garment with fur) was a

most frequently encountered in period sources variety of a sarafan-type dress. Giliarovskaia (p. 98) describes it as a

floor-length garment widened with gores, with straight neck opening,

where a small slit was buttoned using loop closure. The sleeves were very long,

often reaching the hem, but were not actually used. They had arm slits at the

top, and were either simply thrown back or tied one over the other. Fancy shubki were made out of sturdy, heavy

silk brocades, velvets, and other fancy fabrics and lined with silk taffeta.

They were not decorated other than occasional trim along the bottom, but were

worn with a detachable rich collar on special occasions. Plain shubki were made of woolen fabrics or

dyed linen and lined with taffeta only along the hemline. Apparently,

tsaritsa’s shubka was a special

garment, made out of rich golden brocades. It was, in this case, a buttoned

dress with over 15 precious buttons, richly trimmed along the hem, sleeves, and

front opening. The sleeves of tsaritsa’s shubka

were only wrist length, but up to 35 cm wide at the end. This, apparently, was

a derivation of Byzantine-like garments worn by Russian rulers throughout the

period.

|

“Sayan,” “sushun,” and “feriaz’,” three other sarafan-type

garments encountered in period written sources, are better known from

post-period examples (cited here from Sosnina & Shangina). In more archaic

version sayan was made a length of

fabric folded in half, with gores. Arm holes were very wide, and round or

rectangular neck openings were often supplemented by additional vertical slits.

Sushun was similarly made, with a square neck hole and gore-like widening

strips of fabric inserted at the side seams. It’s most prominent characteristic

was the addition of the long, narrow false sleeves at the back of the armholes.

These sleeves were completely non-functional and either tied at the back or

tucked into the belt. Feriazi’, like

sushun, had false sleeves, but was built out of either separate front and back

pieces with gores, or two front and one back pieces with gores. The later type

of feriazi’ could be either sewn shut

at the front, or buttoned with loop closures. Similarity of these garments to

older shubka suggests the likelihood

that their names found in period documents refer to garments resembling these

post-period clothes. |

|

Telogreya

was a button-front dress similar in construction to shubka, and, according to Rabinovich (p. 75), was often worn over

it or over some other sarafan.

Telogreya always had sleeves, either arm length and narrowing to the wrist, or

very long with arm slits at the top. It was very long, down to the heels, and

very wide, about 425 cm at the hem (Giliarovskaia, p. 98). Telogrei usually had a great many buttons (or at least ties), up to

24, which were usually not done all the way. They were extremely dressy, made

of heavy silks, brocades, satins, and velvets, and adorned with gold lace

(usually not made from gold thread but made by jewelers from metal) and other

fancy trimmings. First mention of a telogreia

is found in Kurbsky’s letter to Ivan the Terrible, in the middle of XVIth

century (Rabinovich, p. 76). |

|

One of the

most characteristic women’s garments in period was “letnik” -- a wide, ankle length dress. Its most prominent feature

were wide angel-wing sleeves known as “nakapki.”

These sleeves were floor length, often longer than letnik itself, half as wide as hey were long. They were sewn

together only up to the half-length or a little more, with the lower parts

dangling freely. Nakapki were adorned

with “voshvy,” richly embroidered in

gold and pearls pieces of fabric that was heavier and more expensive than the letnik’s fabric. They were made of about

105-140 cm long, and over 35 cm wide rectangles, cut at the diagonal with

rounded narrow ends. Voshvy were sewn

to the sleeves so that their wider ends were at the wrist, while the narrow

ends dropped down to the hem. In order to

maintain stiffness, they were treated with fish-derived paste from the back

(Giliarovskaia, p. 97). Voshvy were

kept separately, and could be attached to different letniki (Rabinovich, p. 75). Of course, in order to show off the voshvy and to prevent them from

wrinkling, a woman had to hold her hands folded at the waist level, which made letnik exclusively upper class or

special occasion garment.

In addition

to voshvy, letnik was adorned with rich pieces of fabric around the neck and

on the chest, and even at the wrist on top of the voshvy. Winter and fall letniki

(“leto” means “summer” in Russian,

but this was an all-seasons dress) were trimmed with fur (usually beaver’s)

stripes along the hem and at the neck. In cold weather, letniks were worn with a “beaver necklace” – a round fur collar put

on over the head, with hidden slit at the front. The fur was often dyed black

to emphasize the whiteness of the face, and decorated with pearls, gold, and

precious stones. Letniks themselves

were made of a variety of fabrics – cottons, silks, or even gold brocades, with

one-color brocaded silks more prevalent. If there was lining, it was of some

light fabric such as taffeta. Completely fur lined letniki were worn as well, but under separate names – “kortel” or “torlop.” |

|

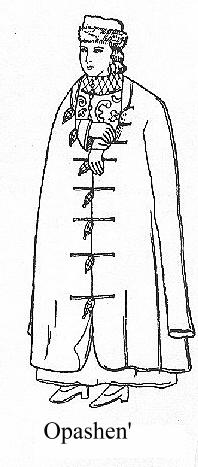

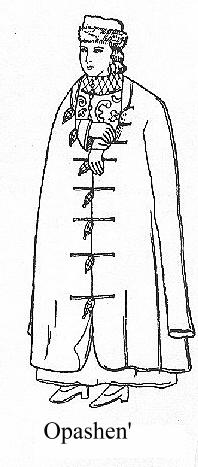

There were several garments that, unlike those already

described, were worn by both genders. A between-seasons garment for fall and

spring, “odnoriadka,” was made of

woolen fabrics without lining (“odin riad”

means “single line” in Russian). It was similar in cut to telogreia, but with hem at the front made shorter than in the back.

Buttons (at least 12) appear to be odnoriadka’s

chief decoration (Rabinovich, p. 76). Another comparable in cut garment, “opashen’, “ was made of summer-weight

silks with silk or cotton lining. Opashen

had arm length or longer sleeves, wide at the top and narrowing towards the

end. It was cut at the neckline on diagonal to make it a continuation of the

front opening (Giliarovskaia, p. 99, Rabinovich, p. 76). Like odnoriadka, opashen had a front that was shorter than the back, but unlike odnoriadka, it was never belted. Opashen, as its name implies in Russian,

was often worn in the summer thrown over the shoulders like a cloak – “naopash.”

Another

unisex garment was “privoloka,” known

as “podvoloka” in XV-XVIIth

centuries. It replaced korzno, a long

cloak that used to serve as a necessary attribute of nobility in earlier

times. Privoloka was relatively short and wide, made of gold brocades with

fancy buttons, and often adorned with gold embroidery of birds and beasts

(Giliarovskaia, p. 99). A women’s privoloka could also be decorated with trim

and voshvy (Rabinovich, p. 78).

Privoloka and similar cloak-type garments were not very popular in described

period, though they gained fashionableness when European styles were introduced

into Russia

by Peter the Great. |

|

Finally, almost any Russian, male or female, rich or

poor, had a “shuba” (from eastern

“dzhubba”). While varied in cut, all shuby

were fur-lined. Poor, both in the city and in the country, had sheepskin shuby not covered with fabric on the

outside, known as “kozhuhi.” Any

well-off person, though, wore a shuba

(and often owned more than one) of carefully selected, often very expensive,

fur covered in rich fabric and adorned with embroidery and gold lace. Even if a

noble had a kozhuh, that kozhuh was fancifully decorated with pearl embroidery

and gold or silver plaques (Rabinovich, p. 78). Though Kireyeva (p. 16 in

Mistress Tatiana Tumanova’s translation) claims that “so inexpensive such fur

was, it was used only for linings,” it appears that fur was worn on the inside

for practical reasons even when it was costly. In fact, other authors don’t

refer to fur as “lining,” but say that it was “covered” with fabrics. Period

written sources mention sable, ermine, and marten furs, none of which were

particularly cheap even in Russia

(Rabinovich, p. 79). Fur was usually used as decoration at all the edges and

for the collar. |

While quite a bit is known about shuby’s materials, their construction did not fare so well. It

appears that the cut and the length varied with time and fashion. All shuby were generally wide garments, but

so-called Russian shuby of XVth

century were cut more to the figure than later Turkish shuby. Russian shuby had

turndown collars and traditional hem-length

sleeves with fur-trimmed slits at the top. They were either buttoned up or tied

with long cords with tassels (Rabinovich, p. 79, Giliarovskaia, p. 71). Turkish

shuby had similar collars but

different sleeves: either wide, wrist length, or double sleeves where one pair

was used and the other, false, hang behind as a decoration (Giliarovskaia, p.

71). Besides different names due to their varied design, shuby had different names due to their varied purposes. For

example, a shuba for sled rides, or “sannaya shuba,” was different from a shuba

for sitting at the dinner table, or “stolovaya

shuba.”

Stolovaya

shuba was not a casual garment

(Kireyeva, p. 17), but a required part of boyar’s and boyaryna’s clothing, worn

in particular to meals in company. Domostroi requires shuby to be worn during various wedding

meals and rituals by all participants in any season, even by the bride and the

groom right after the consummation of the marriage (in that case, “nagolnyye shuby” without fabric cover). Domostroi also requires the

bride and female guests to wear yellow letniki

with red shubki on the day of the

marriage ceremony, white letniki with

red shubki for the guests and white letnik with gold cloth shubka for the bride during the next day

festivities, and the bride to wear a telogreia

to her marriage bed. This suggests that at least some other aspects of life in Russia during

that time were regimented up to the point of what clothes one had to wear –

especially if one happened to be a woman.

Women's Headwear

Women's

headwear, though varied in shape and style, was subject to one of the strictest

regulations: no married woman could be seen in public (and often even at home)

with her hair showing. Maidens, on the other hand, were expected to have at

least tops of their heads uncovered, and were free to show off their hair. They

wore their hair long, parted in the middle and either left free or braided in

loose single braids. During the XVI-XVII centuries, maidens sometimes curled

their hair, perhaps to avoid appearing straight-haired and bring bad luck to

others (Rabinovich, p. 80). Braids were adorned with gold thread, ribbons, or

"kosniky." The later were triangles or other shapes made of

decorative fabric on a stiff foundation and attached to the end of the plait.

Maidens often wore various headdresses made in styles

that left the tops of their heads bare. One of the most common was "perevyazka," a silk or

cloth-of-gold ribbon tied around the head. When the front part of a perevyazka

was decorated with embroidery or pearls, it became "chelo" or "chelka,"

from an Old Russian word for "forehead" (Rabinovich, p. 80). If the

ornamental decoration went all around the head, the headdress (usually on a

stiff foundation) was known as "venok."

Yet another variation,

"venets", was made on a foundation of birchbark or leather with

ornamental cut-outs at the top, in the shape of spikes, embattlements, or

leaves. These cut-outs were known as "goroda," or "cities."

Venets usually had detachable accessories similar to those for married women's

headwear - "riasy" and

"podniz." Riasy were strands of pearls, either

strung in single file or woven/netted, and sometimes adorned with metal

decorations and gemstones. They were attached to a venets or another headdress

at the temples. Podnizi were pearl

nets of varied configurations -in diamond patterns "v refid," in square patterns "reshetkoy" or "kletkami,"

and in chechkerboard pattern "v

shahmat."

Another

semi-shared element of maiden's and married woman's headwear was "chelo kichnoe" - a povyazka that looked like a front part

of a kokoshnik or kika worn by married women, and commonly

misnamed "kokoshnik" in

modern times. According to Giliarovskaia, the name "chelo kichnoe" originates in the XVth century, but a

crescent-shaped or otherwise designed broad povyazka on a stiff foundation with

ribbons at the back was probably known earlier as well.

Married women's headwear usually was composed of many

parts, with only some of them required for all occasions. "Podubrusnik" or "povoynik," a soft light fabric cap

covering a woman's two braids wrapped around the head, was worn under any

additional headdresses. The construction of a period podubrusnik is not clear, but can be inferred from post-period

practices since this and other Russian head coverings remained largely

unchanged throughout the ages. According to Shangina (Sosnina and Shangina, p.

221), a povoynik had a round or oval

cap attached to a relatively narrow border that was gathered on a drawstring

and tied at the back. Alternatively, it could be a made of a single rectangular

piece of fabric gathered at the top of the head and tied at the back with

narrow ribbons. The front of a povoynik

was often embroidered and was allowed to show underneath other head coverings.

In addition to povoynik, women wore

"pozatylnik," a rectangle

of the same fabric as the povoynik covering the nape of the neck. Prior to the

late XIXth century, it was improper to be seen in povoynik alone, even at home,

so it was always worn with "volosnik,"

"ubrus," "kika," "soroka," or "kokoshnik."

A volosnik was simply a net cap with

an embroidered fabric border. It was worn over a povoynik, or either over or under an ubrus. The net was knitted or woven of gold, silver, or silk

threads. The border was made of satin or taffeta in white or shades of red. It

was commonly embroidered in silk or gold thread, and sometimes adorned with

buttons, gems, and dangling pearl attachments (Giliarovskaia, p. 101).

Ubrus,

one of the most ancient Russian head coverings, was an embroidered rectangle of

linen or silk (usually red or white) closely draped around the head, with the

ends left dangling over the woman's shoulders in front and back. Special

decorative pins were used to hold the ubrus

in place (Giliarovskaia, p. 100). A XVIth century ubrus of Anastasia Romanovna, first wife of Ivan the Terrible, is

made of scarlet taffeta 2 meters long. In the front middle part it is adorned

with a blue silk damask rectangle, 40 cm long and 16 cm wide. This rectangle,

"ochel'ie," is richly

embroidered in pearls and gold with enameled inserts. The embroidery runs along

the main body of the ubrus towards

its ends. The ends themselves are trimmed with the endings made of 36.5 cm of

the same fabric with slightly different embroidery (Iakunina, p. 74 and Figure

32). Unfortunately, my source does not allow establishing the width of the ubrus.

When the ubrus was not worn, a married woman's

head was often adorned with a "kika."

A kika was a soft cap surrounded by a

hard "podzor" - a strip of

varied width and shape, often wider on top. According to Giliarovskaia (p.

101), fish paste was used to glue plain fabric to a stiff foundation, all of

which was then covered in satin or other silk fabric. The front of the podzor (mentioned earlier chelo) was decorated as richly as the

owner's income allowed. At the back a piece of velvet or a sable skin covered

the nape of the neck, while at the front pearl riasy and a podniz

emphasized the whiteness of the wearer's skin.

"Soroka" and "kokoshnik" are the headdresses

mentioned in XVI-XVIIth century written sources, but the details of their

construction in period can only be inferred from headdresses of the same names

worn in Russia

through the XIXth century (Rabinovich, p. 81). Rabinovich also suggests that

some kind of stiff-based headwear similar to a kokoshnik existed before the XIIIth century, even if it was not

known by that name. Sosnina and Shangina (p. 309) refer to soroka as to one of the most ancient Russian headdresses, spread

all over Rus' since the XIIth century. They describe post-period soroki as multi-part headdresses

incorporating a plain kika-like hat

in various shapes covered with a fancy shell, soroka proper. Like kika,

it included a pozatylnik. Soroka was

sewn of several parts, known as "chelo,"

wings, and a tail, the word "soroka"

itself means "magpie" in Russian.

While soroki could be of any shape in any

region, Sosnina and Shangina (p. 117) describe 4 territorial types of kokoshniki. In Central Russia (Moscow, Vladimir,

etc.) there existed three variations of a single-horned kokoshnik. The best known and probably oldest version had a soft

back and a high, hard front shaped like a crescent with rounded edges or sharp

edges lowered to the shoulders. The front of such a kokoshnik was adorned with gold and pearl embroidery, and sometimes

with gemstones. The back was also commonly embroidered in gold. Single-horned kokoshniks usually had pearl podniz attached to cover the forehead

almost to the eyebrows. In the North-West (Novgorod, Tver', etc.) kokoshniki were cylindrical, or pillbox-shaped. They also had podnizi, and pozatylniki (like kiki), as

well as small earflaps. The third type of kokoshniki

also existed in some Northern regions, though not widely spread (and most

likely not at all in period). Such a kokoshnik

had a flat oval top, a protuberance over the forehead, earflaps, podniz, and a pozatylnik. Finally, in

the South, a kokoshnik was

two-ridged, or saddle-like. Its top was slightly elevated in the front and

higher in the back, like a saddle. It was worn in combination with a "nalobnik" - a narrow strip of

ornamental fabric tied around the head, as well as a pozatylnik. This type of kokoshnik also does not appear to be

period. All 4 types in the XIII-XIXth centuries were commonly worn with "platok," a square of decorative

fabric, which leads to a suggestion that period forms of them could be worn

with ubrus or other similar head

coverings. It is worth noting that kokoshniki

were considered to be very fancy headdresses, and were highly valued and passed

down through generations.

Of special interest is a tsaritsa's

headdress, "koruna." Koruna was a venets, a crown,

surrounding a round hat topped with a precious gem or a cross and ornately

decorated (Giliarovskaia, p. 101, 103). This was a headdress not to be worn by

anyone else, and only worn by tsaritsa herself on state occasions.

Giliarovskaia cites a memoir of Arseniy, bishop of Elasson, who visited Moscow in 1588-1589.

Arseniy describes a koruna worn by

Tsaritsa Irina: "On her head she wore a blindingly shiny crown, which was

artfully put together of precious stones and divided with pearls into 12 equal

towers for 12 apostles…. In the crown, there were a great many carbuncles,

diamonds, topazes, and large pearls, while it was surrounded with large

amethysts and sapphires. Besides this, on both sides from it dangled tripled

chains (riasy) made of precious

stones and covered in such large and expensive emeralds that their value and

price were beyond compare." While this was, of course, a hat meant only

for royalty, this description provides an idea of the general grandeur of

female headwear, where everything was overdone as far as the owner's income

could allow.

The great

variety of women's headwear was replaced during cold months of the year (most

of the year in some parts of Russia)

by "shapki." However, this

name united another medley of hats that had in common their basic two-part

construction of fabric crown and fur surround. The crown could be round,

conical, or cylindrical. Depending on the income, it was made of various

materials, from plain wool to gold velvets adorned with pearls, gems, and

embroidery. The fur part extended lower in the back for married women, to cover

all their hair, while maidens wore well-rounded hats (Giliarovskaia, p. 101). A

popular kind of a hat, "stolbunets,"

was a rather tall cylinder narrowing towards the top. A special-occasion "gorlatnaya shapka" was worn by maidens and by a bride the day after her

wedding, even indoors (Domostroi). This was usually a male hat, made of the

precious neck fur of rare animals ("gorlo"

means "neck" in Russian.) It was tall, cylindrical, and widening

towards the top (Rabinovich, p. 84). The very top was usually made of fabric.

Accessories (belts, jewelry, etc.)

A belt was

a very important element of Russian costume, be it boyar’s or peasant’s. Many

garments required a belt, and when several of such garments were worn in

layers, a man or a woman could be sporting several belts as well (Rabinovich,

p. 84). Most common belts were woven, braided, or twisted, and used to belt a

rubakha or a sarafan. Belts of a

similar construction were still in use in Russian countryside up to XXth

century (Sosnina and Shangina; Rabinovich).

Coats and

other upper garments were belted with leather belts or with wide fabric “kushaki.” Buckles and metal decorations

(tips and plaques) for leather belts are common finds in archeological digs

(Rabinovich, p. 83). Note that the buckles were not unlike the modern ones, and

had a tongue. Kushaki, on the other hand, were made of bright fabrics with

specially decorated ends. High nobility wore precious gold belts as well, and

such belts were often listed in Great Dukes’ wills.

Since neither

men nor women had pockets (men’s clothing acquired detachable pokets, “kisheni,” and sewn-on pockets, “zepi,” by the end of the period), belts

served to hold various objects, just like in the West. A belt box of precious

metal, “kaptorga,” or a leather pouch,

“kalita” or “moshna,” could serve as a purse. Kalita was not unlike purses worn on a belt or over the shoulder in

Western Europe, except that it was highly

ornamented.

While most

garments were collarless, separate collars known as “ozherelya” were either attached (with buttons or ties) or simply

worn over some of them. Such embroidered in silk, gold, and pearls collars were

made of rich imported fabrics or of furs. One type of ozherelya was round and lay flat on the shoulders, either with

opening at the back or with hidden closure. Another was a standing collar

attached to shuby or letniki.

Similarly,

separate from clothing cuffs, “zarukav’ia,”

were worn by both men and women on the wrists, holding up shirts’ sleeves. They

were made of imported fabrics and embroidered in gold and/or pearls, sometimes

with addition of gemstones. Zarukav’ia

belonging to nobles are mentioned in period written sources (Rabinovich, p.

86), but only surviving examples are zarukav’ia of high church officials (see

Iakunina or Manushina for illustrations).

Women in

period usually did not wear gloves. During the cold season, the poor used

mittens for work, while women from the upper classes hid their hands either in

warm long sleeves or muffs ("rukavki").

According to Giliarovskaia (p. 102), rukavki

were quite narrow and made of silk, velvet, brocade, or gold cloth, with fur

lining and often lots of gold and pearl embroidery and even gemstones. Men wore

mittens or gloves, which could be made of soft leather, velvet, or silk, and

either sewn or knitted. The gloves or mittens of the rich were usually

fancifully decorated, especially along their cuffs and, on mittens, along the

back of the hand. There were "warm," (fur-lined,) and

"cold," (fabric-lined,) mittens and gloves. (Rabinovich, p. 90,

Giliarovskaia, p. 82.)

A necessary

attribute of a woman's wardrobe was a "shirinka"

- a handkerchief embroidered in silk or gold (sometimes pearls as well) and

trimmed with fringe and tassels (Giliarovskaia, p. 102). Shirinki were not only decorations, but displays of a woman's

craftsmanship, so they were often very elaborately made. There are several

examples of shirinki dated to the

XVI-XVIIth centuries in the Zagorsk Museum collection, all of them square or

almost square, ranging from 45 to 55 cm, with double-sided embroidered borders

(Manushina)

Apart from

clothing-related decorations, noblewomen possessed numerous items of jewelry,

such as earrings, rings, necklaces, and chains, not to mention headwear

accessories such as riasy. On the

neck, women wore “monisto,” a

necklace of various beads or pearls, and metal plaques (Pushkareva, p. 168).

Pearls in particular were very popular, and sometimes worn in multiple strands.

Chains were very valuable adornments, and could be made with links of various

shapes. They were often used to hold a cross, something no woman was without.

Finally, an older type of neck jewelry, “grivny,”

still existed in described period, though perhaps they were no longer very

popular (Pushkareva, p. 168, Rabinovich, p. 87).

Earrings

were almost a necessity for any women. They were made as gold or silver open

rings or hooks with attachments made of wire with metal beads or gems.

Depending on the number of attachments, in later period earrings were known as

“odintsy,” “dvoyni,” or “troyni”

(Rabinovich, p. 87). According to Sosnina and Shangina, “troychatki” or “troyni”

with three attachments became popular in XVth century (p. 320), while “dvoychatki” with two were known in the

central and northern Russia

since the end of the XVIth century (p. 70). They also claim that the term “odintsy” is known since the late XVIIth

century, in the same region (p. 195).

Various

rings were very popular, and are among the most common archeological finds.

They could be braided, twisted, or made of interconnected plates. Signet rings

made an appearance in the XIIIth century, and were decorated with animals,

birds, and geometric shapes. They remained in wide use at least until XVth

century, along with Novgord rings with colored glass inserts (Pushkareva, p.

172).

Finally,

women wore various bracelets, though those appear to be waning in use as

compared to earlier centuries. They could be glass or metal (copper, bronze,

silver, or gold), with latter appearing in many shapes and styles. The bracelets

were worn at the wrist or on the upper arm, sometimes several together and on

both arms at once (Pushkareva, p. 173).

Footwear

Peasant men

and women, just like in the earlier times, predominantly wore “lapti” with “onuchi” – woven bark shoes over cloth wraps. Lapti were made either from inner bark of foliose tress (usually

linden), or from birch bark. To make one pair of lapti for a woman (and women in period had small feet) three or

four young linden trees had to be used. Usually lapti, even with a double sole, wore out in a week at best.

Sometimes lapti were made from

leather strips, and while they lasted longer, they were also more expensive

(Pushkareva, p. 172).

Another

form of lower class’ footwear, “porshni,”

was in use in the cities as well as in the countryside. According to Rabinovich

(p. 50), porshni were commonly made

from a single rectangular piece of leather (not tanned, just kneaded and

oiled). The corners of a rectangle were connected in pairs, and a leather thong

was then threaded around the top edge. More rare archeological finds are those

of porshni made from two pieces of

leather. Sometimes porshni were

decorated with cutouts or embroidery, in which case they could also be lined

(Pushkareva, p. 173). According to Pushkareva, the seams on porshni were made with waxed linen

thread, and ornamental seams in this thread could be used to decorate everyday porshni. Porshni for women were usually of softer leather than those for

men. Porshni, like lapti, were secured by means of thongs

crisscrossed along the lower leg and tied below the knee.

The city

dwellers preferred to wear “choboty,”

“chereviki,” and “sapogi.” “Sapogi” were mid-calf length boots, while “choboty” and “chereviki”

were shorter (Rabinovich, p. 88). The archeologists find choboty and chereviki

that either are embossed or have lacy cutouts. Rabinovich (p. 89) speculated

that the latter probably had colored thread laced through the holes to create

patterns. Most choboty and chereviki were black, but fancier ones

could be in bright colors and made of materials pother than leather – morocco,

satin, or velvet, often embroidered.

Sapogi were the most popular form of

footwear in the cities. Rabinovich (p. 89) cites an ambassador to the Russian

court, baron Gerbershtein, who visited Moscow

in late 1500s and wrote: “They wear mostly red and very short boots, so that

they don’t reach the knee, and the soles are nailed with metal nails.” Sapogi were made of varied kinds of

leather, and could be not only black or red, but also green or yellow,

especially if made from morocco. They were often embossed, with complicated

patterns on the bootlegs and simple lines imitating natural folds on the lower

front parts. Throughout the described period sapogi could be embroidered in silk or gold, and later in pearls as

well. Often they had bright, fancy fabric cuffs at the top. (Rabinovich, p. 89,

Pushkareva, p. 174)

More

ancient shoes were made from thin leather and were soft, with soles made from

several layers of leather. While sapogi

made in this fashion still existed even in the XVIIth century, hard soles made

an appearance in the XIVth century. This was also the time when footwear became

asymmetric, and not the same for both feet. The soles were sewn to he shoes and

secured with nails, as well as with a little horseshoe at the heel. At the back

most shoes, except for women’s half-boots, had birch bark inserts. Until the

XVIth century all footwear was flat-soled. The high and medium-high heels were

then made of multiple layers of leather, often secured with a metal brace and

protected from wear with a horseshoe at the bottom. The toes of sapogi and choboty, depending on the regional fashion, could be round or

pointed, with the latter often raised and secured to a special slit at the top

of the boot’s front (Rabinovich, p. 89).

Most people

wore their sapogi or other footwear

over onuchi, wool or cloth wraps that could be fur-lined in winter. Sometimes “nogovitsy” – leg-warmers, and knee

coverings were added to onuchi. Sewn and knitted stockings of varied length (“chulki”) became more widespread during

this period. Knitted stockings probably appeared in the XVth century, and could

be either made locally or imported. The stockings were held to the legs with

ties. (Rabinovich, p. 90)

Men’s clothing and headwear (brief notes)

The base for all male dress

ensembles was the shirt, "sorochka,"

(also called "srochka",

"scrachitsa", etc. in

period), described in detail in the "Undergarments" section. In

addition to the shirt, men wore "porty" - narrow cloth trousers that

clearly outlined the legs and were always worn inserted into sapogi or onuchi. (Rabinovich, pp. 44,

68.) Porty extended below the knees

but didn't quite reach the ankles. (Rabinovich, p. 44.) By the end of the

described period, porty were completely

relegated to the role of underwear, and outdoors were worn topped with outer

pants which could be made of fancy fabrics, leather, or even fur. The exact cut

of these pants, however, is not known. (Rabinovich, p. 70.)

Referring

to other authors, Rabinovich (p. 70) suggests that throughout this period men

wore a "zipun" over their

undershirts and under other layers of clothing. A zipun was a short, narrow jacket with narrow sleeves. Its

construction, however, is not well documented in period sources. Like "kaftan," the word "zipun" is Turkish and could have

entered the Russian language either from Turkey or through the Tatar

invaders.

Kaftan was men's outerwear (rarely -

women's as well), for use at home or outdoors in warm weather. The word itself appeared

in written sources in the XVth century, and by the XVIIth century came to refer

to a variety of garments united by their basic design - a lined, buttoned coat,

at least knee-length, where the right front opening covered the left front

opening. Kaftany were made shorter in

the front than in the back, so that they would show off the boots and not

interfere with walking. The sleeves could be either the type with arm slits at

the top (made in the upper part of the sleeve, on the seam, or at the armhole

seam under the arm), where the dangling sleeves are thrown back or tied

together at the back, or wrist length sleeves, in which case they were worn

with zarukav'ia (ornamental cuffs).

The Turkish

kaftan was long, loose in cut, with

very long but relatively narrow sleeves worn either scrunched up on the arm or

dangling, with arms coming out through openings at the top. It buttoned only at

the neck, had a narrow standing collar, and was usually worn belted.

(Giliarovskaia, p. 70, Rabinovich, p. 72.) Dressy ("vyhodnoy") kaftan,

also long, was worn either buttoned up or open, over a zipun. The sleeves of

such kaftany were wide, and only

wrist length. Dressy kaftany were

made of light weight silk fabrics with lining (which could come out to the

outside of the garment, forming borders at the edges), decorated with gold and

silver metal lace. (Giliarovskaia, p. 70.) Several other types of kaftany appeared in the late XVIIth

century and will not be discussed here.

Terlik,

another one of kaftan-type garments,

was a favorite of Ivan the Terrible. It was more narrow than other kaftany, fitted at the waist (sometimes

with the top part cut separately). The loop-and-button closures run to the

waist from collarless triangular neckline, with lower part of the front opening

left unbuttoned. At the neck, along the opening, the hem, and around the

sleeves terlik was usually decorated

with fancy trim, gold cord, pearls, and even gemstones (Giliarovskaia, p. 71). Terliki could also be made with fur lining, and worn with

separate fur collars 12 cm wide. This was a garment suitable for state

occasions until the XVIIth century, when it became a service uniform.

"Feriaz" was a kaftan-type garment that was ankle length, without a waist-line,

and with long sleeves, narrowing to the wrist. It could also be sleeveless. The

feriaz was worn over another kaftan by the upper classes, over a

shirt by commoners, and was either left open or buttoned to the waist with long

decorative horizontal button and loop closures. Buttons were round or egg-shaped,

made of metal (often gold or silver) and sometimes incorporated gemstones. Feriazi were made from cottons and

silks, as well as from wool, velvet, and brocade, with metal lace or trim

decorations, sometimes applied in double rows along all the edges. In addition,

appliques of tasseled cord were used as adornments for feriazi, which lacked any kind of collars. Feriazi could be lined with fabric or fur. (Giliarovskaia, p. 73,

Rabinovich, p. 74.) Outdoors, commoners often wore loose coats made from

homespun wool known as "armiak,"

from the Persian "urmak.” These

coats were similar in design to feriazi,

and existed in the wardrobes of nobility as well, made for them from more

costly fabrics. (Rabinovich, p. 77, Giliarovskaia, p. 77.)

As mentioned earlier, both men and

women wore odnoriadki, unlined loose

coats with long sleeves, and opashni,

(sing. - opashen'), similar in cut to

odnoriadki but with lightweight

lining. Men also could wear an okhaben’

or opashen' - odnoriadka with a large fold-down square collar. Okhabni were sometimes worn over the

shoulders, like mantles, and had long, thrown back sleeves with underarm slits.

(Rabinovich, p. 76, Giliarovskaia, p. 71.) Men wore the actual mantles or

capes, privoloki, as well. This

garment, along with odnoriadka and opashen, is described in the women's

clothing section, together with shuby,

the fur-lined coats worn by men in the winter.

During the XIIIth century, men

commonly wore their hair loose and almost shoulder length. In the north, this

style changed in the XIV-XVth cc to long braided hair. The XV-XVIIth centuries

brought short haircuts, cut round or square at the back, and even shaved heads.

The short hair may be related to the custom of wearing "tafia," a skullcap, at home and

under other hats. (Rabinovich, p. 83.) At this time, long hair was worn by the

clergy and by those in disfavor with the tsar. Long, wide beards were always

popular, though shaving was common as well, until Ivan the Terrible decreed it

to be illegal. (Giliarovskaia, p. 82.)

In the

XIII-XVIIth centuries, especially towards the end of this period, the "kolpak" was the most popular form

of men's headwear. A kolpak was a

tall conical cap turned out at the bottom to form a sort of a cuff, which could

have one or two holes for attaching decorations: buttons, clips, tassels, or

fur trimmings. (Rabinovich, p. 83.) Kolpaki

were either knitted or sewn of any kind of fabric, depending on the owner's

income. There were kolpaki for

sleeping, wear at home, everyday and dress wear. (Rabinovich, p. 83.)

Those well

off could also wear "murmolki"

- tall caps shaped like cut cones with fur borders fastened to the crown in two

places with loops and buttons. Murmolki

were made of silk, velvet, or brocade, and decorated with metal plaques. (Rabinovich,

p. 84.) Late period boyars also wore tall fur caps known as "gorlatnaya shapka," as described in the women's headwear section. Among

fur caps of the time, there was a "treuh"

or "malahay," a round

flat-topped cap with three flaps similar to modern Russian fur hats.

(Rabinovich, p. 84.)

Children's Clothing

Period

written sources mention items of children's clothing for the wealthy - the same

shirts, kaftany, and shuby as adults wore (Rabinovich, p.

96). It is, however, reasonable to propose that Giliarovskaia (p. 11) is right

to claim that children of the poor ran around just in shirts, regardless of

their gender. Archeologists also find child-sized sapogi and other footwear, with some evidence that they could have

been made from worn-out adult footwear. (Rabinovich, p. 96.) The Domostroi (Old

Russian version, p. 42; Pouncy trans. p. 128,) recommends being careful when

cutting out children's clothing, and to allow reserves at all the seams and at

the hem for growth, to be let out as needed. This advice, however, is only for

"dress that is not to be worn daily," since simple clothes would not

last the five or six years desired by Domostroi.

Note: Pouncy's translation of this passage mentions specific

items of dress which are not listed in the original Old Russian text. The

original says: "And if you happen to cut any dress ("platno") for a young son or

daughter, or a young daughter-in-law, be it men's or women's dress, anything

good, then when cutting, allow two or three inches ("vershka") at the hem, and at the edges, at the seams and at

the sleeves; when they grow up, two, three, or four years later, rip the seams

and straighten the allowance, and the dress will fit again, for 5 or 6 years.

Cut this way anything not worn all the time."